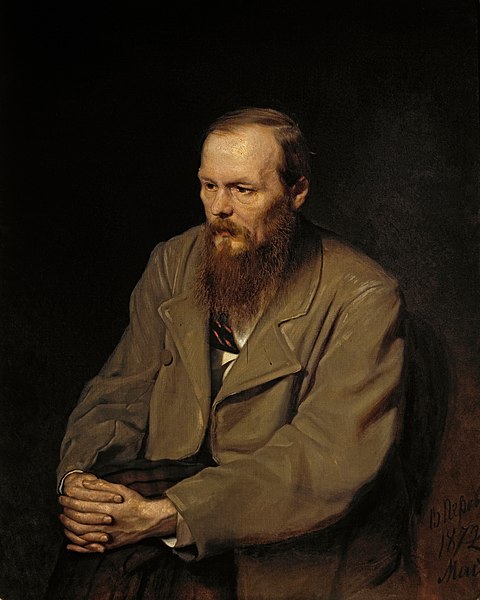

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Life, Gambling Addiction, Roulette.

- Greg Walker

- 20 Mar 2021

Fyodor Dostoevsky is one of the world’s greatest novelists, and for eight years of his life he was addicted to roulette. It was during this time that he wrote Crime and Punishment.

The following is a summary of his life, along with the details of his gambling addiction based on his private letters and a book he wrote called The Gambler.

Life.

Fyodor Dostoevsky was born on 20th October 1821 near Moscow.

From an early age he took an interest in books and writing, but at the age of 16 his father sent him to an engineering college. His mother died that same year, and two years later his father died as well. Despite losing both parents and having the desire to write, he continues with engineering college and graduates at the age of 22.

Fyodor was now free to pursue his literary career.

At the age of 25 he writes and releases his first book, Poor Folk, which is written in a unique format where two lovers write letters to one another. The book is a great success, and it propels him on to the literary scene in Russia. However, his second book The Double (written that same year), is met with deeply negative criticism and he is ridiculed by those who once praised him.

Then at the age of 28, he is arrested and sentenced to death.

He had joined a small group of intellectuals two years prior called the Petrashevsky circle. The group discussed social and political topics, and a smaller group within it secretly campaigned for the freedom of the serfs (similar to slaves). However, the government infiltrated the group and arrested all of the members, including Fyodor.

He spends a year in solitary confinement, before finally being sentenced to execution by rifle.

On the day of his exection he is led out to the place where he is going to be shot. The first three prisoners are led out and tied to the posts. He is sixth in line. He realizes that he has only minutes of his life left.

But just before the order to fire, the execution is halted.

His sentenced is commuted to hard labour at the last moment. But still, he had sincerely believed that he was going to die.

He spends the next 4 years of his life in Siberia, living alongside criminals and peasants in utterly grim conditions. He cannot write during this time, and lives only to survive. However, at the age of 33, his four years of hard labour come to an end, and he moves on to indefinite service in the Russian army instead. Then after a further five years (and with the help of friends), Dostoevsky is finally able to leave the army as a free man.

He is now 38.

He restarts his literary career by writing the House of the Dead, which is a dark account of his time spent in the prison camp in Siberia. This is published a year after his release, and quickly brings him more fame than his first book. He also starts publishing a literary magazine called Time with his brother, which provides them both with financial stability. Things are going good, and he travels to Europe for the first time a few years later in 1862 at the age of 41.

But the following year the magazine is forced to close. There had been a misunderstanding with the government about an article he and his brother had published concerning Russia. Dostoevsky travels to Europe again in the summer nonetheless, and experiences his first loss at the roulette wheel. He is reduced to pawning his possessions to survive, and writes letters (Letter 2) to friends and family requesting money.

Whilst back in Russia in April 1864, his first wife dies. And two months later, so does his brother.

I have been crushed by life.

A cold, lonely old age and epilepsy are all that lie ahead for me.

He invests all of the money he has in to the new magazine Epoch that he and his brother had started before he died. He also unwisely assumes all his brother’s debts, which means his financial freedom is tied to the success of the magazine. The overwhelming debt and workload of keeping the magazine running shatters his health, and the magazine collapses a year later due to lack of funds.

In his desperation, Fyodor signs a merciless contract with a publisher named Stellovsky that requires him to deliver a book within a year, else he will lose the rights to anything he writes for the next nine years. Using the funds from this contract, he escapes to Europe.

He revisits the roulette tables upon his return to Europe. He has the hope of winning enough money to free himself from his debts and to return to Russia. And as a result, he loses all the money he has.

This marks the start of the darkest period of his life.

It’s during this time he conceives the idea for Crime and Punishment; a story about a man who convinces himself that murdering an old lady is a good idea, and the subsequent horrors of living with his actions. Whilst writing this book he also writes The Gambler in the space of a month (to satisfy his contract with Stellovsky), which documents his experiences of gambling and is essentially a narration of his own addiction to roulette.

The following years are the most chaotic of his life. He struggles with living abroad, his worsening epilepsy, and having to work within the throes of a gambling addiction that regularly reduces him to despair.

But in his strife to achieve financial freedom, he writes three of his greatest literary works: Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1868), and Demons (1871). And it's in 1871, after a foreboding dream and another cutting loss at the roulette wheel, that he resolves to never gamble again.

And this time he keeps his word.

He spends the remaining years of his life from 1871 at home in Russia. These are comparatively calm years, although his worsened epilepsy means that he is often unable to write for days or weeks at a time. Nonetheless, in 1880, at the age of 59 he begins releasing his final book The Brothers Karamazov, to great critical acclaim.

He sends the last section of the book to his publisher in November 1880.

Two months later, on 28th January 1881, Fyodor Dostoevsky died.

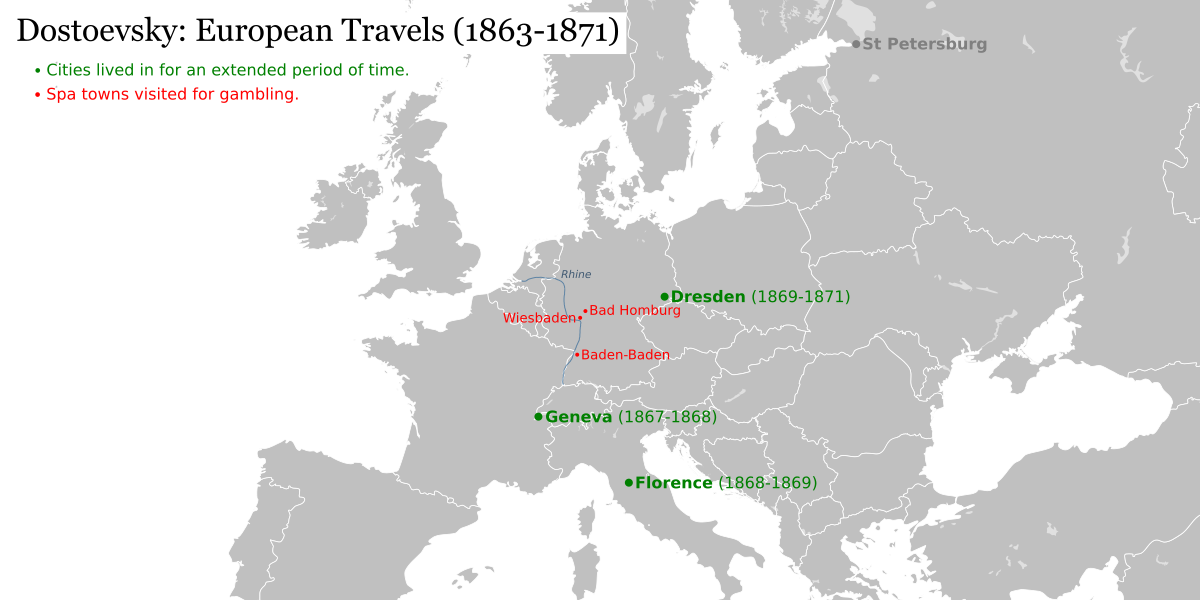

Map.

The following map shows the places Dostoevsky stayed whilst living in Europe, along with the locations of the towns he visited for playing roulette.

The most notorious location for his gambling was in Wiesbaden.

His home was St Petersburg.

Timeline.

|- 1821: Birth |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- 1837: Mother dies. Sent to Academy of Engineering. |- |- 1839: Father dies. |- |- |- |- 1843: Graduates from engineering school. |- |- |- 1846: Poor Folk. |- |- |- 1849: Imprisoned and sentenced to death. |- 1850: Starts hard labour in Siberia. |- |- |- |- 1854: Finishes hard labour and continues sentence in military. |- |- |- |- |- 1859: Resigns from military, sentence is over. |- 1860: Restarts literary career. House of the Dead. |- |- 1862: Travels to Europe. |- 1863: Travels to Europe. First sign of gambling addiction. |- 1864: Notes from the Underground. Wife dies. Brother dies. |- 1865: Financial ruin. Travels to Europe to escape creditors. |- 1866: Crime and Punishment, The Gambler. |- 1987: Marries second wife. Leaves Russia for Europe to escape creditors. |- 1868: The Idiot. |- |- |- 1871: Demons. Stops gambling. Returns to Russia. |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- |- 1880: The Brothers Karamazov. |- 1881: Death Key: | = Years in Academy of Engineering. | = Years in Siberian exile. | = Years of gambling addiction. Book. (Not all books are included - just the major and relevant ones.)

Gambling Addiction.

Dostoevsky wrote many letters to family and friends during his lifetime, and some of those letters contain personal accounts of his gambling addiction.

During this time the majority of his gambling took place at spa resorts (which commonly had casinos at the time) along the river Rhine in Germany, most notably; Wiesbaden, Bad Homburg, and Baden-Baden.

Below are excerpts from some of the letters he sent between 1863 and 1871.

Letter 1 (1863)

This is the first letter that shows Dostoevsky’s interest in gambling.

In this letter to his wife’s sister, he begins by telling her about winning money in Wiesbaden. This will become a frequent destination for him over the next eight years.

He describes his approaching to playing, and how he believes he is able to beat the game.

Date: September 1, 1863

Location: Paris

[...]

During those four days, Varvara Dmitriyevna, I had a good look at gamblers. There were several hundred of them placing their stakes there and, I give you my word, there weren't more than two of them who knew how to play. They all were losing their shirts, because they didn't know how to play. But there was a Frenchwoman and an English lord — those two knew how play and they were not losing; on the contrary, they almost broke the bank. Please do not think that, in my joy over not having lost, I am showing off by saying that I possess the secret of how to win instead of losing. I really do know the secret — it is terribly silly and simple, merely a matter of keeping oneself under constant control and never getting excited, no matter how the game shifts. That's all there is to it — you just can't lose that way and are sure to win. But the difficulty is not in finding this out, but in being able to put it into practice once you do. You may be as wise as a serpent and have a will of iron, but you will still succumb. Even Philosopher Strakhov would have succumbed. And so, blessed are those who do not gamble and look upon roulette with disgust, as the most idiotic thing there is.

[...]

Later in the letter Dostoevsky tells Varvara that he will be sending her some of his winnings, which he does.

However, a week later he gambles and loses the rest of his winnings, and asks her for some of the money back.

Note: It’s during this trip abroad that Dostoevsky conceives the idea for his novel The Gambler. Both a Frenchman and an English lord appear as characters in the book. However, the book is not written until 1866 (three years later).

Letter 2 (1863)

This letter is written around the same time as asking for some of his winnings back from his wife’s sister.

It is written in reply after informing his brother about his gambling losses (and also asking him for money). At this time he is in Turin, and has recently pawned his watch for money. He is travelling with his mistress who has also pawned her ring.

In the main body of the letter he explains to his brother how he managed to lose so much of his money at the roulette wheel.

Date: September 8/20, 1863

Location: Turin

[...]

You ask in your letter how a man can gamble away his last kopek, especially when he is traveling with someone he loves. Let me tell you, my dear Misha, that in Wiesbaden I devised a system of play which I put to the test and won myself 10,000 francs [$39,254]. But the next morning in my excitement I failed to stick to my system, and lost right away. In the evening I went back to my system, stuck strictly to it, and quickly and effortlessly won 3,000 francs again [$11,776]. Now, tell me yourself, after this happened how could I help getting carried away, how could I fail to believe that as long as I held hard and fast to my system, happiness was in my grasp? And I need money — for myself, for you, for my wife, to enable me to write my novel. Here people win tens of thousands just like that. Yes, I came here hoping to save you all and to stave off misfortune. And then, too, I had faith in my system. And what's more, when I got to Baden, I walked up to the roulette table and won 600 francs [$2,355] within a quarter of an hour. That whetted my appetite. Suddenly I started losing; I could no longer restrain myself and lost everything I had with me. After I sent you the letter from Baden, I took the last money I had and went back to play. I started with four napoleons [$314] and won 35 napoleons [$2,748] within half an hour. This extraordinary pice of luck went to my head, and I risked those 35 napoleons and lost the whole 35. After paying the landlady, we had six gold napoleons [$471] left for hour journey. In Geneva, I pawned my watch.

[...]

Letter 3 (1865)

At this time Dostoevsky’s brother had died the year before, and Dostoevsky is left with heavy debts due to their failed magazine.

He travels again to Europe to escape his creditors, and has done so using money he acquired by signing the risky Stellovsky contract. This contract would see him losing the rights to his work for nine years if he doesn’t produce a book in a fixed amount of time (which eventually ends up being The Gambler).

In this letter he appeals to Turgenev for money, who is an old literary friend who he is on good terms with at the time. He starts by explaining his dire financial situation due to the magazine's failure, before swiftly moving on to his request for money because of further losses at the roulette wheel.

This is one of Dostoevsky’s shorter letters.

Date: August 3/15, 1865

Location: Wiesbaden

[...]

But two years ago in Wiesbaden I won around 12,000 francs [$47,105] within a single hour. Although this time I did not expect gambling to be a panacea, it would have been very pleasant indeed to win 1,000 francs [$3,925] or so to tide me over for at least three months. I arrived in Wiesbaden only five days ago, and I have lost everything already, just everything, including my watch, and I even owe money to the hotel.

I feel loathsome, and ashamed to be bothering you with my affairs. But I really have no one else right now to whom I can turn and, in the second place, you are much more intelligent than the others, and so it is morally easier for me to turn to you. Here is what I have in mind: I am asking you, as one human being to another, for 100 (one hundred) thalers [$1,488]. I am expecting a bit of money from Russia, from a magazine (Library for Reading), which they promised to send me when I left, and also from one gentleman who must help me. It is quite unlikely that I can pay you back before three weeks; then again, it might be earlier. In any case, a month at the latest. I feel horrible inside (I thought it would be worse) and, above all, I'm ashamed to bother you, but what can you do when you are drowning?

[...]

Turgenev sends him the money.

Letter 4 (1867)

By now Dostoevsky has recently married his new wife Anna, a stenographer who helped him to finish writing The Gambler (to satisfy his contract) whilst also in the middle of writing Crime and Punishment.

In the spring of this year they both travel to Europe to escape continued harassment from Dostoevsky’s creditors, but this time on a more permanent basis. During this time he frequently leaves his new wife to visit gambling casinos in an attempt to win enough money to free himself of his debts and return to Russia.

The following is one of many letters he sends to his new wife about his losses at roulette.

Date: Wednesday, May 22, 1867, 10AM

Location: Bad Homburg

[...]

Forgive me, my angel, but I must go into some of the intricacies of my venture, of the game, so that you will see more clearly what it is all about. Already on twenty or so occasions I have observed as I approached the gaming table that if one plays coolly, calmly and with calculation, it is quite impossible to lose! I swear — it is an absolute impossibility! It is blind chance pitted against my calculation; hence, I have an advantage over it. But what usually happened? As a rule, I would start with forty gulden [$116], I would take them out of my pocket, sit down, and stake one or two gulden [$6] at a time. Within a quarter of an hour, I would usually (always) double my money. This was the moment to have stopped and left, at least until the evening, so as to calm one's excited nerves (furthermore I have made the observation — and thoroughly substantiated it — that I can never maintain my coolness and detachment in gambling for longer that half an hour at a time). But if I left the table it was only to go out for a smoke and then rush back to the game.

Why did I do it, knowing almost for sure that I wouldn't be able to restrain myself, i.e., that I would lose? It was because I told myself, on getting up in the morning, that this would be my last day in Homburg, that I would be leaving on the morrow, and that therefore I couldn't waste any time in getting to the roulette table. I pressed myself hard to win as much as I could in a single day (since I was to leave the next day), and I lost my composure, became tense, started to take chances, became exasperated, laid my bets haphazardly because my system had broken down then — and lost (because anyone who plays without a system, relying upon sheer chance, is a madman). The whole mistake was for us to have parted and that I didn't bring you along with me. Yes, yes, that's what it is. So here I am, missing you badly, while you are almost dying without me. My angel, I repeat — I am not reproaching you for anything and you are even dearer to me for being so miserable without me. But judge for yourself, my sweet, by what happened to me yesterday, for instance.

After mailing my letter in which I asked you to send me money, I went to the casino. I had only twenty gulden [$58] left in my pocket (that I had kept for an emergency), and I risked ten gulden [$29]. I made an almost superhuman effort to stay calm for a whole hour and to play systematically, and ended up winning thirty gold fredericks, i.e. 300 gulden [$868]. I was so elated and felt such a terrible and maddening urge to finish with it all that very day, to win at least as much again, and leave this town right away that, without giving myself a chance to draw breath and recover my senses, I rushed back to the roulette table, started laying stakes in gold — and I lost everything, the whole lot, down to the last kopek; or to be more exact, I was left with two gulden [$6] for tobacco.

Anya, my darling, my joy! Try to understand that I have debts that I must pay and that people will say that I am a scoundrel. Try to understand that I shall have to write to Katkov and then sit around in Dresden and wait. I simply had to win. It was essential! I am not gambling for my amusement. Why, that was my only way out — and now everything is lost because of a miscalculation. I am not blaming you, but I'm cursing myself for not having brought you along with me. If you gamble in small doses every day, it is impossible not to win. That is true, absolutely true, and experience has proved it to me twenty times over. And it is with this knowledge that I am leaving Homburg as a loser; and I also know that if I could give myself just four more days, in those four days I surely could win everything back. But I most certainly won't go and gamble now!

My sweet Anya, please understand (I implore you once more) that it is not you, not you, whom I'm blaming. On the contrary, I blame myself for not having brought you along.

[...]

Letter 5 (1867)

Dostoevsky continues to lose money at the roulette wheel whilst living abroad.

This (longer that usual) letter is sent to another old literary friend, and for the first time feels like a confession of his addiction to gambling.

Date: August 16/28, 1867

Location: Geneva

[...]

[...] But now I shall tell you the despicable and disgraceful things I did.

My dear Apollon Nikolayevich, I feel that I can trust myself to your verdict as my judge. You are a man and a citizen, you are a man with a heart, a fact of which I became convinced a long time ago. You are an exemplary husband and father, and, finally, I have always valued your judgement. I don't mind confessing to you. But I am writing this for you alone. Do not subject me to the judgment of other men!

Since Baden was not too far out of my way, I took it into my to stop over there. A tempting idea plagued me: to risk 10 louis d'or [$785] in the hope that I might wind up with an extra 2,000 francs [$7,851], which, after all, would take care of us for 4 months, everything included, and would also cover my expenses in Petersburg. The most disgusting thing about it is that I had won on some previous occasions. And the worst part of it is that I have a vile and overly passionate nature. Everywhere and in everything I drive myself to the ultimate limit, all my life I have been overstepping the line.

And right away the devil played a trick on me: In three days or so, I won 4000 francs [$15,702] with incredible ease. Now let me tell you how I visualized the whole situation: On the one hand, there was that easy win — in three days I had turned a hundred francs [$393] into four thousand [$15,702]. On the other hand, debts, lawsuits, anxiety, the impossibility of going back to Russia. And, finally, the third and the most important point — the gambling itself. You know how it ensnares you. No, I swear, it is not just avarice, although I did need money for money's sake above all. Anna Grigorevna pleaded with me to content myself with the 4000 thousand [sic] francs [$15,702] and to leave at once. But then it was such an easy and opportune occasion to set everything aright! And one sees such examples. Besides your own gains, you witness daily others picking up 20,000 [$78,508], 30,000 francs [$117,762]. (You don't see those who lose.) What's so saintly about them? I need money more than they do. I took the risk, went on playing, and lost. I went on to lose every last thing I had; in my feverish exasperation, I lost. I started pawning clothes. Anna Grigorevna pawned everything she had, down to the last knickknack. (What an angel she is, the way she tried to cheer me up! How lonely she felt in that accursed Baden, in the two small rooms over a blacksmith's to which we had moved.) In the end — that was that — everything was lost.

[...]

Later in the letter he asks Maivov to send him money.

Letter 6 (1871)

Dostoevsky and his wife remain in Europe after four years abroad. He has completed his books The Idiot and Demons in what has been the most chaotic period of his literary career. But now they are both making preparations to return to Russia.

However, Dostoevsky returns once again to Wiesbaden to play roulette, and loses. In this raw and heartfelt letter to his wife, he confesses to his loss and promises that he will never gamble again.

Date: Friday, April 16/28, 1871

Location: Wiesbaden

[...]

Now Anya, you may believe me or not, but I swear to you that I had no intention of gambling! To convince you of that, I will confess everything to you: when I wired you asking you to send me 30 thalers [$372] instead of 25, I thought I might yet risk another 5 thalers [$74], but I was not sure I would do even that. I figured that if any money were left over, I would bring it back with me. But when I got the 30 thalers today, I did not want to gamble for two reasons: (1) I was so struck by your letter and imagined the effect it would have on you (and I am imagining it now!) and (2) I dreamed last night of my father and he appeared to me in a terrifying guise, such as he has only appeared to me twice before in my life, both times prophesying a dreadful disaster, and on both occasions the dream came true. (And now, when I think of the dream I had three nights ago, when I saw your hair turn white, my heart stops beating — ah, my God, what will become of you when you get this letter!)

But when I arrived at the casino, I went to a table and stood there placing imaginary bets just to see whether I could guess right. And you know what, Anya? I was right about ten times in a row, and I even guessed right about Zero. I was so amazed by this that I started gambling and in 5 minutes won 18 thalers [$268]. And then, Anya, I got all excited and thought to myself that I would leave with the last train, spend the night in Frankfurt, and then at least I would bring some money home with me! I felt so ashamed about the 30 thalers [$446] I robbed you of! Believe me, my angel, all year I have been dreaming of buying you a pair of earrings, which I have not yet given back to you. You had pawned all your possessions for me during these past 4 years and followed me in my wanderings with homesickness in your heart! Anya, Anya, bear in mind, too, that I am not a scoundrel but only a man with a passion for gambling.

(But here is something else that I want you to remember, Anya: I am through with that fancy forever. I know I have written you before that it was over and done with, but I never felt the way I feel now as I write this. Now I am rid of this delusion and I would bless God that things have turned out as disastrously as they have if I weren't so terribly worried about you at this moment. Anya, if you are angry with me, just think of how much I've had to suffer and still have to suffer in the coming three or four days! If, sometime later on in life you find me being ungrateful and unfair toward you — just show me this letter!)

By half past nine I had lost everything and I fled like a madman. I felt so miserable that I rushed to see the priest (don't get upset, I did not see him, no I did not, nor do I intend to!). As I was running toward his house in the darkness through unfamiliar streets, I was thinking: "Why, he is the Lord's shepherd and I will speak to him not as to a private person but as one does at confession." But I lost my way in this town and when I reached a church, which I took for a Russian church, they told me in a store that it was not Russian but [Jewish]. It was as if someone had poured cold water over me. I ran back home. And now it is midnight and I am sitting and writing to you. (And I won't go to see the priest, I won't go, I swear I won't!)

[...]

Anya, I prostrate myself before you and kiss your feet. I realize that you have every right to despise me and think: "He will gamble again." By what, then, can I swear to you that I shall not, when I have already deceived you before? But, my angel, I know that you would die(!) if I lost again! I am not completely insane, after all! Why, I know that, if that happened, it would be the end of me as well. I won't, I won't, I won't, and I shall come straight home! Believe me. Trust me for this last time and you won't regret it. Mark my words, from now on, for the rest of my life, I will work for you and Lyubochka [second child] without sparing my health, and I shall reach my goal! I shall see to it that you two are well provided for.

[...]

But what can happen to me? I am tough to the point of coarseness. More than that: it seems as if I have been completely morally regenerated (I say this to you and before God), and if it had not been for my worrying about you the past three days, if it had not been for my wondering every minute about what this would do to you — I would even have been happy! You mustn't think I am crazy, Anya, my guardian angel! A great thing has happened to me: I have rid myself of the abominable delusion that has tormented me for almost 10 years. For ten years (or, to be more precise, ever since my brother's death, when I suddely found myself weighted down by debts) I dreamed about winning money. I dreamt of it seriously, passionately. But now it is all over! This was the very last time! Do you believe now, Anya, that my hands are untied? — I was tied up by gambling but now I will put my mind to worthwhile things instead of spending whole nights dreaming about gambling, as I used to do. And so my work will be better and more profitable, with God's blessing! Let me keep your heart, Anya, do not come to hate me, do not stop loving me. Now that I have become a new man, let us pursue our path together and I shall see to it that you are happy!

[...]

Dostoevsky never gambles again.

The Gambler. (Book, 1866)

The Gambler was written by Fyodor Dostoevsky in 1866. He wrote the book whilst in the middle of writing Crime and Punishment.

Dostoevsky had the idea to write a novel about gambling in 1863 after his first experience of losing money at roulette.

Just as House of the Dead attracted the attention of the public because it was a portrayal of convicts, who had never been portrayed graphically by anyone before, so this story is bound to attract attention as a graphic and very detailed representation of gambling at roulette.

―Fyodor Dostoevsky (Letter to N. N. Strakhov, 1863)

He intended for it to be a full-length novel like his other works, but he ended up using the idea three years later as a way to fulfill a contract on short notice instead.

You see, due to financial problems in 1865, Dostoevsky agreed to a dangerous contract with a publisher named Stellovsky, where he was required to provide a book by 1 November 1866 or else lose the rights to his work for the next nine years. He had not written anything by October, so he quickly wrote the book (~60,000 words) within a space of a month, and handed it over on 31 October 1866.

The story is heavily based on his own experiences of gambling, and focuses on his time spent in Wiesbaden (Germany) in 1863.

Plot.

This short book is about a wealthy Russian family on holiday at a town called Roulettenburg in Germany.

The family is facing financial ruin (not gambling related), and are awaiting the death of their elderly Granny so that they can inherit her wealth. However, during the course of their stay their Granny makes a surprise visit to the town, and proceeds to lose millions at the roulette table, leaving the rest of the family facing destitution.

The story is told from the perspective of the main character Alexey, who is a tutor employed by the family. Like many of Dostoevsky’s characters, he is deeply interesting yet not entirely likeable as a person.

Later in the book Alexey becomes addicted to roulette himself, and loses sight of the girl he loves in the process.

Quotes.

Although the main focus of the story revolves around the relationships in the family, there are a handful of vivid chapters describing roulette. In between the characters and storyline, Dostoevsky reveals his own feelings toward roulette and his understanding of gambling addiction.

I speak to relieve my conscience.

The following are quotes from chapters that have a focus on gambling.

Chapter 2.

In this chapter the main character Alexey visits the casino to play roulette for the first time.

I had to study the game; for, in spite of the thousand descriptions of roulette which I had read so eagerly, I understood absolutely nothing of its working, until I saw it myself.

He briefly questions the lack of virtue in winning money as opposed to earning it.

And why should gambling be worse than any other means of making money — for instance, commerce?

He gives his impressions upon entering the gambling saloon.

In the first place it all struck me as so dirty, somehow, morally horrid and dirty. I am not speaking at all of the greedy, uneasy faces which by dozens, even hundreds, crowd round the gambling tables. I see absolutely nothing dirty in the wish to win as quickly and as much as possible.

There was no sort of magnificence in these trashy rooms, and not only were there no piles of gold lying on the table, but there was hardly any gold at all.

He describes the behaviour of gamblers, as well as the differences between them.

What was particularly ugly at first sight, in all the rabble round the roulette table, was the respect they paid to that pursuit, the solemnity and even reverence with which they all crowded around the tables.

It is most charming when people do not stand on ceremony with one another, but act openly and above board.

A real gentleman should not show excitement even if he loses his whole fortune.

Chapter 4.

In this chapter the Alexey plays roulette on behalf of Polina, who is a member of the family that he has fallen in love with.

He describes his approach to playing:

I kept quiet and looked on; it seemed to me that calculation meant very little, and had by no means the importance attributed to it by some players.

I drew one conclusion which I believe to be correct, that is, though there is no system, there really is a sort of order in the sequence of casual chances — and that, of course, is very strange.

After winning money through a series of successful bets, he begins to find himself engaged in the game:

At that point I ought to have gone away, but a strange sensation rose up in me, a sort of defiance of fate, a desire to challenge it, to put out my tongue at it.

This compulsion leads him to lose all the money he had won up to that point.

Later, when being chastised by other family members for playing roulette, he defends his actions by declaring how the accumulation of wealth by honest toil is a vice in itself:

I can't endure honest people whom one is afraid to go near.

I want money for myself, and I don't look upon myself as something subordinate to capital and necessary to it.

Chapter 10.

Alexey accompanies Granny as she goes to the casino for the first time. Granny starts playing roulette, and decides to bet on zero. She loses at first, before winning two times in a row (with the second winning bet being much larger than the first).

Alexey describes his emotions after helping Granny to place those winning bets:

I was a gambler myself, I felt that at the moment my arms and legs were trembling, there was a throbbing in my head.

Shortly after, he describes Granny before she makes two final bets on red for all her money:

She was, if one may so express it, quivering inwardly. She was entirely concentrated on something, absorbed in one aim.

Granny wins both times. They leave the casino.

Chapter 12.

After her large win, Granny decides to play roulette the next day.

Granny was in an impatient and irritable mood; it was evident that roulette had made a deep impression on her mind.

She bets on zero again, but continues to lose. After multiple failed attempts she switches to betting on red, and this time zero turns up. In her rage she increases her stake, and eventually loses all the money she had won the day before.

Granny makes Alexey help her to exchange more of her money so she can gamble with it, and in her desperation accepts a bad exchange rate. They return to the casino, and Granny loses much of it. They both leave, and Granny vows to return to Moscow.

However, shortly after, Granny returns to the casino alone with the remaining money.

As sure as I'm alive, I'll win it back.

She loses again.

Chapter 13.

Alexey describes how Granny returned to the casino once more in his absence, but this time with all the money she had taken with her on her trip:

The following day she lost everything. It was bound to happen. When once anyone is started upon that road, it is like a man in a sledge flying down a snow mountain more and more swiftly.

He describes her play:

I marvelled how she could have stood those seven or eight hours sitting there in her chair and scarcely leaving the table, but Potapich told me that three or four times she had begun winning considerably; and, carried on by fresh hope, she could not tear herself away.

But gamblers know how a man can sit for almost twenty-four hours at cards, without looking to right or to left. Granny had played late in to the night, and in the process was taken advantage of by spectators around the table who attached themselves claiming to be of help.

The family’s financial future is ruined, and Granny returns to her estate in Moscow.

Chapter 14.

Polina and Alexey speak privately, and he begins to realize she may love him after all. But in his misguided elation, he chooses to return to the casino alone in an attempt to win money for her.

Sometimes the wildest idea, the most apparently impossible thought, takes possession of one's mind so strongly that one accepts it at last as something substantial.

He embarks upon an incredible winning streak, and becomes frenzied as he bets larger and larger amounts during his session:

I staked the last four thousand on "passe" [the numbers 19-36 in French Roulette] (but I scarcely felt anything as I did so; I simply waited in a mechanical, senseless way) — and again I won; then I won four times running.

I don't remember whether I once thought of Polina all this time.

He proceeds to break the bank on two roulette tables, before moving to a game called Trente en Quarante, and wins more again.

I was possessed by an intense craving for risk.

Perhaps passing through so many sensations my soul was not satisfied but only irritated by them and craved still more sensation — and stronger and stronger ones — till utterly exhausted.

Eventually he leaves and returns to Polina with his substantial winnings, who is sat at home in front of a candle with her arms crossed.

Chapter 17.

The story concludes a year and a half later. Alexey has lost Polina, and finds himself ruined by his addiction, having no other occupation other than gambling.

He confirms his addiction:

Even on my way to the gambling hall, as soon as I hear, two rooms away, the clink of the scattered money I almost go in to convulsions.

And his degenerated experience of winning large sums of money:

Yes, at moments like that one forgets all one's former failures! Why, I had gained this by risking more than life itself, I dared to risk it, and — there I was again, a man among men.

In the final pages, Alexey meets with an old friend, who confirms that Polina did indeed love him after all, but who was now mentally unwell. He talks in no uncertain terms about how Alexey has destroyed himself through his gambling addiction.

You have not only given up life, all your interests, private and public, the duties of a man and a citizen, your friends (and you really had friends) — you have not only given up your objects, such as they were, all but gambling — you have even given up your memories.

After parting with his friend, Alexey finishes by recalling a story of a recent experience at the roulette wheel… He was down to his last dollar, and decided to leave the casino to use it to buy food. However, before leaving, he returned to bet it on the wheel instead, and won.

He concludes:

What if I had not dared to risk it?

Review.

I assumed The Gambler was going to be a deep personal account of one man’s descent and fight against gambling addiction. But this is not the case. At the heart of the story is the family and the relationships they have with one another and in society, and the experiences at the roulette table are secondary.

The story itself isn’t as gripping as the likes of Crime and Punishment, and whilst the characters are unique and intriguing, they are not as memorable as ones from his other books. This is probably due to the fact that the book needed to be written within a month, so Dostoevsky didn't have the time to give it the same planning or depth as his other works.

Nonetheless, Dostoevsky’s analysis of gambling addiction in parts of the book are exemplary. He captures the atmosphere of the casino, and describes the behaviour of gamblers disturbingly well. His insights in to gambling addiction (he wrote the book in 1866) are as accurate today as anything that has been written since.

Even though the book isn’t my favorite, it’s a fascinating opportunity to read the thoughts of someone as masterful as Dostoevsky as they reveal their own addiction to gambling through the medium of fiction.

Conclusion.

Dostoevsky suffered from his addiction to gambling. During one of the most successful periods of his literary life he was reduced to writing letters to family and friends imploring them for money, and having to pawn his own possessions to survive. He also compelled people he loved to pawn their clothes and jewellery to support him too.

If nothing else, it’s a fascinating insight in to how gambling can take someone away from who they really are.

Dostoevsky’s addiction was driven by a desire for freedom. He wanted to free himself from his debts so badly that he was prepared to risk his own ruin in the process. All that stood between him and returning home to Russia was the roulette wheel, and he convinced himself that he could win if only he played well enough.

My one aim is to be free. I'd sacrifice anything for freedom.

And that’s the disturbing part; that a man of Dostoevsky’s genius could fool themselves in to believing they could beat the odds by their own force of will.

He was smart enough to know the odds were against him. He studied engineering when he was younger, so he would have been aware of the mathematics of the game (and the fact that the house had the edge). Still, his dreams of winning were so overpowering that he ignored logic and created a fantasy in his own mind where he could beat the game if only he could control his composure.

I really do know the secret — it is terribly silly and simple, merely a matter of keeping oneself under constant control and never getting excited, no matter how the game shifts.

But the mathematics beat him just like it beats everyone else.

Fortunately his addiction between 1863 and 1871 did not wipe out his ability to write. In fact, he wrote three of his greatest works during this time: Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1868), and Demons (1871). It’s possible that the crushing situation he found himself in drove him to write with more determination than ever before, and these books are the product of a man working for his own mental freedom.

Yet what’s equally as interesting as his addiction is his departure from it.

He manages to free himself after one particularly bad experience in 1871: a combination of a foreboding dream involving his deceased father, another devastating loss at the hands of the wheel, and almost visiting a Synagogue afterwards (he was not Jewish), seems to be enough to make a deep impression on him. Dostoevsky believed in omens, and this one was too dark to ignore.

His change of perspective was unusual and sudden, but it’s clear that at that moment, for whatever reason, he believed that his gambling addiction was about to lead him to lose more than money.

And for that reason he never gambled again.

Notes.

Currency exchange rates.

The following table gives a rough estimate of the exchange rate for the different currencies of the time in terms of their current value in USD (2020). I do not believe these values are exact, but I thought a rough estimate would be better than nothing.

| Germany | Gulden | $2.89 |

|---|---|---|

| Thaler | $14.88 | |

| Friedrich D'or | $28.92 | |

| Switzerland | Franc | $3.93 |

| Louis D'or | $78.51 |

- The original exchange rates are taken from the notes section of Selected Letters of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, which gives the values in terms of USD at the time (I'm assuming for the year 1863). The values in their table are gathered from Herman Schmidt, Tate's Modern Cambist: A Manual of Foreign Exchanges and Bullion ... (London: Wilson).

- The inflation rate between 1863 and 2020 was 1,965.71% . (Source: https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1863)

- The book does not contain the exchange rate for friedrich d'ors. However, in Dostoevsky's letter to Anna in 1867 he says that he won "thirty gold fredericks, i.e. 300 gulden", so I'm assuming that 1 friedrich d'or is worth 10 gulden.

- The book does not contain the exchange rate for "napoleons" either, but according to wikipedia a napoleon is commonly worth 20 francs, which would make it the same value as a louis d'or.

Sources.

- The excerpts of Dostoevsky's letters are from Selected Letters Of Fyodor Dostoyevsky (Joseph Frank and David I. Goldstein, 1989) (ISBN-10: 0813511852, ISBN-13 : 978-0813511856).

- Quotes from The Gambler are taken from the translation by Constance Garnett. Newer translations provide a smoother and more modern read, but I like this particular translation for standalone quotes.

- My recommended translation of the book for reading is the one by Jane Kentish (ISBN-13: 978-0-19-953638-2). It also includes a discussion of Dostoevsky's gambling in the introduction by Malcolm Jones.